+44 7957 770386

Blog

Let's face it, just as gaining ISO 27001 Certification became all but mandatory to win and retain contracts in a post-GDPR world, it is likely that ISO 22301 Certification will become similarly desirable in a post Covid-19 world. If you are familiar with ISO 27001, you will know that business continuity is already an important part of compliance with that ISO Standard. It talks about protecting information assets and data in the event of a disruptive incident. When the dust settles, business in the UK are going to know exactly when, why, how and for how long they suffered during the disruptive incident that was instigated by the Coronavirus, Covid-19. Beyond maintaining information security, actual business survivability became the key concern. Broader business continuity management, which spans the entire spectrum of your critical business activities is going to be essential in a post Covid-19 world. • How has each of your diverse business functions faced the Covid-19 crisis? • What departments were the most resilient in the short term? • When did business-as-usual become business during an emergency? • What functions needed extra support from other departments as the crisis changed and extended? • Did you deploy the right people, resources and technology in the right place and at the right time? • How did you know how to prioritise where and when to spend money on recovery? You may not have realised, but these are all questions to be considered as part of business continuity management. Your approach to business continuity needs to be multi-faceted, taking into account how each critical activity has a different recovery point objective (RPO), recovery time objective (RTO) and maximum tolerable period of disruption (MTPD), which may place different challenges on effective resource distribution and use, at different times, during the next disruptive incident. What might good business continuity management look like in a post Covid-19 world? • Leaner business models - a laser focus on non-essential costs • Increased virtualisation - 'virtual' offices and remote working • Increased collaboration with key suppliers • More support for bring your own device (BYOD) - as businesses struggled to source and distribute existing IT equipment • Increased pressure from stakeholders to have third-party approval of their approach to BCM, such as ISO 22301 Certification At Consultanci, we will assist you through the process of establishing, implementing and certifying a resilient approach to business continuity management (BCM), which fits your organisation and at the right pace for your compliance team.

We are living in an age where charities are under more scrutiny than arguably any other time in living memory. The sector has been rocked by high profile scandals from industry standard-bearers Oxfam and the WWF, seen acrimonious and very public shutdowns (Kids Company) and had to weather waves of bad publicity due to controversial approaches to data management and direct marketing tactics. Public support has dipped, with fewer people giving to charity than previously. Furthermore, although overall levels of trust haven’t changed too much over the past few years, they remain at their lowest since way back in 2005, with a long-term increase in the number of people who are saying their trust has decreased. And those who feel they cannot trust charities as much as they once could are donating less as a result. The lesson? Trust is crucial for charities to fundraise — and even operate — effectively. In the wake of this comes the new approach from the Fundraising Regulator, where the subject(s) and details of a complaint are made public. The decision was made by the Board of the Fundraising Regulator back in October 2018 and came into effect on 1 March 2019. The first set of 10 named investigation summaries was issued earlier this month, with the list including some industry big-hitters, with Macmillan Cancer Support, Alzheimer’s Society, The Salvation Army and the NSPCC all among those listed. Transparency is becoming ever more important in the sector. Now that the Fundraising Regulator is bringing its approach more in line with that of the Charity Commission (which has publicly named organisations subject to investigations since June 2014), what could easily be a name-and-shame exercise at a time when charities need it least, has become an opportunity for the sector to start rebuilding public trust at a time when charities need it most. A crucial element of the naming process is that it’s not just charities in the dock, but also the private companies they often enlist to undertake fundraising activities on their behalf. While not held in the same regard as charities, these fundraising companies nevertheless carry the reputation of charities in their hands whenever they interact with the public, be it in the street, on the doorstep or over the phone. So, to include them in a public naming complaints process will only help to draw a clearer line between the two types of organisation. Why is this important? Put simply, in the event the fundraiser was in breach of the Code of Fundraising Practice, it reduces the reputational damage done to a charity with relatively little control over the behaviour of contracted fundraisers operating in their name. Of course, it is a charity’s responsibility to do its due diligence when selecting an agency, but that can only go so far — which is why the Regulator is needed. In addition to the ability to separate the charity from blame, this new approach also clearly details the steps taken to date and what is expected next from the organisations involved. This will not only improve accountability, but it also gives any interested members of the public rare insight into what is being done to improve the way funds are generated — especially at bigger charities. As a rule, the general public can reasonably accept mistakes will be made, as long as some learning and positive change comes out of the situation. Of course, it may mean there will be uncomfortable conversations to be had, and potential public relations issues to be managed, but if that is what it takes to get the public back on side, then, in the long run, it can only be a good thing. Originally published at https://www.charitytoday.co.uk on October 24, 2019.

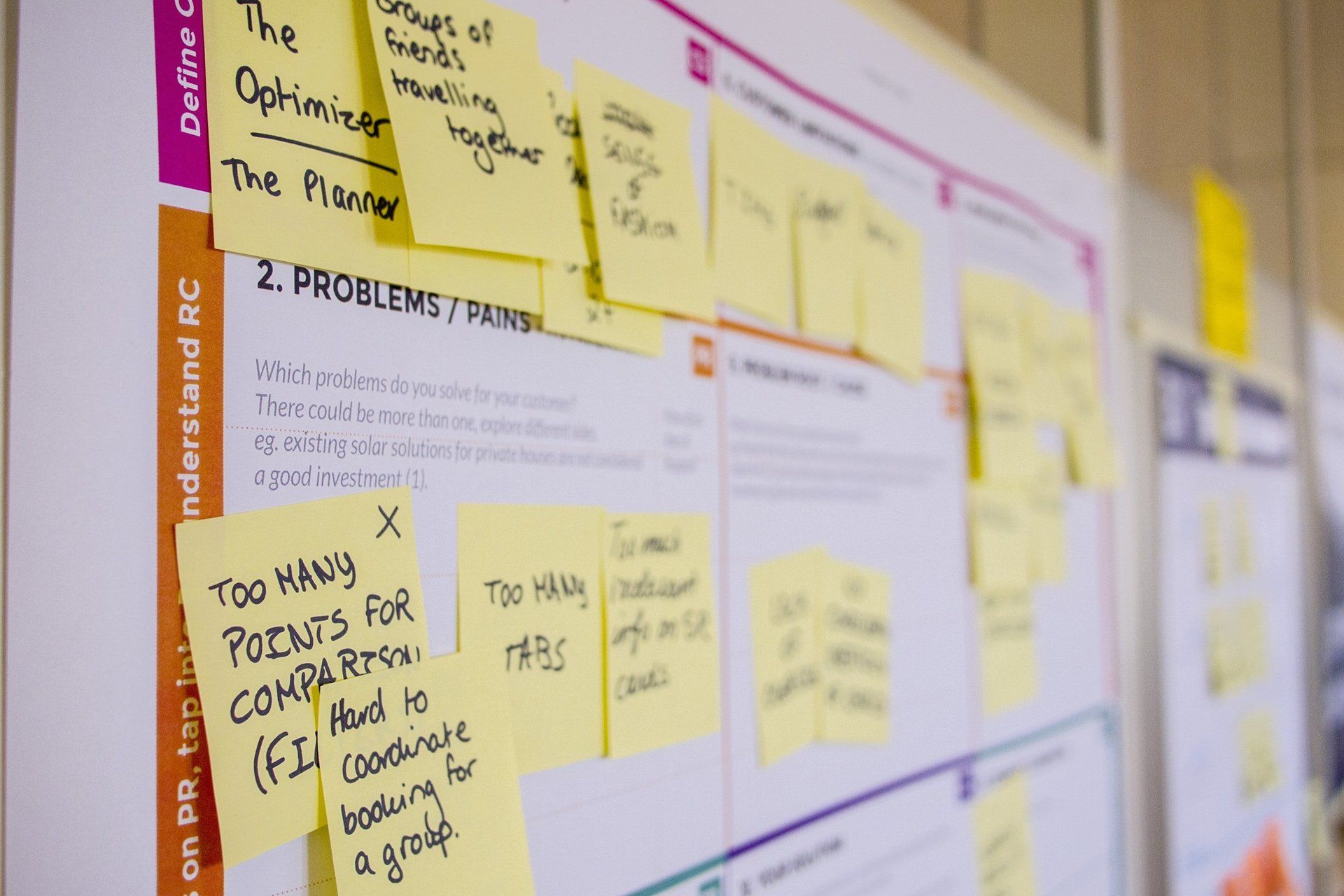

When working as a consultant, you rely on your ability to identify and secure customers. Your existence depends on it. But having worked as a service provider for a reasonable portion of my career, I've learnt that business development and the process of finding and onboarding new customers, clients or partners is rarely what you think it might be. While it may seem a fairly straightforward proposition, providing the kind of support to organisations that I do invariably involves a far more nuanced approach to business development than I admittedly thought it would be at the beginning of my career. Thankfully, one thing which has definitely become easier is confidence in my abilities and the confidence to value it accordingly - both of which are hard-earned and born out of experience. But even with a well-founded belief in your skills and a proven track record in delivering results, there are often additional hurdles to overcome before you can get off the starting block. Thus begins what I call the 'process of illumination'. We all have doubts which need addressing. And whether working with startups or organisations operating in the not for profit space, there is an understandable cautiousness when it comes to parting with vital funds. So, part of the process of illumination is addressing these doubts, fears and reticence in order to progress the conversation further. I've also always believed part of my role is to de-mystify what I do. I've never wanted to be 'gatekeeper', operating shrouded in mystery. Instead, I like to see myself as more of a tour guide. Of course, there are levels of depth when it comes to explaining what I do and how I do it, but I want the organisations I work with to have a good grasp of what they are paying for. Despite what some might think, 'pulling back the curtain' doesn't put the value of my offer at risk, either. Just because you know how something works doesn't mean you can recreate or do it yourself. And I don't see that I'm selling to customers - but working collaboratively with partners, so we need to be on the same page and working together if we're going to see results. It's a lot easier to bring someone along with you on the journey if they not only have a good idea of the destination, but also the route being taken to get there. The process of illumination as I refer to it is the means via which organisations who work with me understand the part my offer plays in them realising their goals. Just as important, though, is the process through which I gain a fuller understanding of their needs and whether I'm the right person to support them. I've learnt from experience there's nothing worse than swimming upstream with a customer with whom you don't see eye to eye. If at the end of the process both parties don't feel confident enough to proceed, I'm always happy to signpost them to other providers or options that might better suit their needs. If, however, all goes to plan then getting the ball rolling is a hell of a lot easier. Trust me, I'm a professional!

Public safety and response • The public are prepared to talk to fundraisers despite the pandemic which is positive. • Showing the public that appropriate PPE (Government recommended PPE) is consistently being used and on display is building public confidence. • Contactless mandate processing is working well and is something expected by new donors. • Often fundraisers are being asked by the public why they are back out fundraising F2F despite the pandemic not being over. • Daily pictures of fundraisers showing full PPE is useful evidence of compliance to risk assessments. • Risk assessments should be continually referred to and where appropriate, updated in order to keep in-line with changing Government guidelines. • Copies of risk assessments are being requested by Local Councils to evidence compliance and ensure public safety. • Regular checks of infection rates / geographical hotspots are a good idea as they are impacting fundraising https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/#category=utlas&map=rate • Reviewing and avoiding areas of local lockdown is essential e.g. Leicester, Blackburn and Darwin. Private Site / Street fundraising • Access to Private Sites has and continues to be very challenging. • Footfall and therefore conversations are substantially down (reduced by circa 50%) at Private Sites resulting in reduced donor recruitment averages, particularly on Regular Giving campaigns (1 – 1.5 new donors per fundraiser / day). • A reduction of almost 80% in Street Fundraising activity versus pre COVID 19. D2D fundraising • Licensing Councils are continuing to allow F2F fundraising activity but it must be in-line with IOF and Government guidelines. • Averages new donor recruitment on D2D is similar to prior to the pandemic (2.5 – 3 new Regular Giving donors and 5 – 6 new Lottery players per fundraiser / day) with more conversations taking place as more people are home due to the pandemic. • There has been a substantial increase in D2D fundraising (circa 50% more than pre-COVID 19) activity which could present more clashes and pressure on territory going forwards which needs to be considered. • Territory planning to avoid households with a higher propensity of potentially shielding donors is an important consideration. Fundraising performances • Masks and visors are making it sometimes hard for fundraisers (steaming up, voice projection, length of conversation, maintaining energy levels). • Daily feedback from fundraisers is really valuable and where possible should include number of stops / doors opened, number of interactions, public comments both positive and negative as well as how the day has gone from the fundraisers perspective. • Initial performances are being achieved by the most experienced fundraisers as part of the initial test re-start activity. Results could be diluted when more fundraisers go out with less experience. • Potential new donors are keen to support but want a lower ask i.e. under £10 or variable ask per month on Regular Giving campaigns. • There has been quite a strong desire from new donors to show their support through giving a one-off donation as opposed to a regular financial gift. • Fundraisers are working shorter shifts in less locations which is providing “breathing space” for the public. • Telephone fundraising continues to build momentum with the development of more F2F fundraisers becoming more competent at this channel of fundraising instead of F2F fundraising due to a lack of F2F activity / furloughing.